by Wanda Sabir

Happy Mother’s Day! The mothers honored include Mother Earth (smile) and incarcerated mothers, especially those mothers whose children were stolen or adopted out and are now lost to their families.

Congratulations to all graduates, whether this is from one grade to the next, from a vocational program or from a college or university. Education is a lifelong endeavor. Knowledge is power!

Save the date: International Libations for the Ancestors, second Saturday in June, June 10, 8:30 a.m. We start at 9 a.m. exactly. It is a simultaneous libation. Everyone is pouring at the same time. In the San Francisco Bay Area, we meet at the fountain at Lake Merritt, Lakeside Drive and East 18th Street, across from the old Merritt Bakery; Out of the Closet is across the street too. Visit maafasfbayarea.com and remembertheancestors.com.

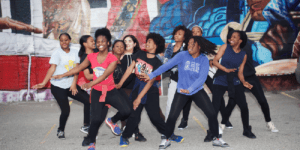

‘The Village Matters’

Clik here to view.

Dimensions Dance Theatre presents its annual youth showcase, “The Village Matters,” on Sunday, May 7, at 4 p.m., in the Phillip Reeder Auditorium at Castlemont High School, 8601 MacArthur Blvd., Oakland. Tickets are $10-$20. Group discounts and a limited number of advance free tickets are available to students and teachers within Oakland Unified School District. Contact 510-465-3363 and dimensionsdance.org. For tickets, visit Eventbrite.com.

Participants include Rites of Passage, Dimensions Extensions, LIKHA School of Philippine Dance, On Demand, BAY-Peace, Oakland Technical High School, Oakland High School, Bret Harte Middle School and Kipp Bridge Academy. The program also features guest artists Destiny Muhammad, “Harpist from the Hood,” and Batalá San Francisco.

Listen to a recent interview with Deborah Vaughn, co-founder and artistic director of DDT. Find out how you can financially support Dimensions in a special fundraising drive, East Bay Gives, through Thursday, May 4.

Dance benefit

The Sankofa Akili Dance Fundraiser, on Saturday, May 6, 1-4 p.m., at Defremery Recreation Center, 1651 Adeline St. in West Oakland, features Avotcja, Bisola Marignay, Vulindlela and Nozipo Wobogo, Ron Williams, Tacuma King, Stones of Fire, Wanda Sabir and more.

Jazz films

Films to catch quickly at the Roxie in San Francisco: “I Called Him Morgan” (2017) April 28-May 4, a new film by Swedish director Kasper Collin tells the story of 33-year-old jazz trumpet star, Lee Morgan, who was shot by his wife, Helen. The film’s narrative is an interview with Helen upon her release with of course archival performances and interviews with artists and critics. The director is known for his profile of another jazz musician, My Name is Albert Ayler. Like Morgan, Ayler, saxophonist, also had an unexpected and violent end, his body found in New York’s East River. He was 34. Deeply spiritual, one of his well-known works is the album, “Spiritual Unity,” and the selection “Ghosts: First Variation.”

“Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary” (2017), directed by John Scheinfeld, is screening at the California in Berkeley and the Landmark Embarcadero and Rialto in Sebastopol through May 3.

Clik here to view.

W. Kamau Bell’s new memoir

Saturday, May 6, W. Kamau Bell, comedian, political commentator, TV and radio show host, will be reading from and discussing his new book, “The Awkward Thoughts of W. Kamau Bell: Tales of a 6’4” African American, Heterosexual, Cisgender, Left-Leaning, Asthmatic, Black and Proud Blerd, Mama’s Boy, Dad, and Stand-Up Comedian,” at Mrs. Dalloway’s Bookstore at the Starline Social Club, 645 W. Grand Ave. in Oakland. Tickets are $30-$40.

Bell will be joined in conversation by Adam Mansbach, the award-winning novelist, writer and cultural critic behind “Go the Fuck to Sleep,” “Rage is Back,” “Angry Black White Boy” and more.

25th anniversary of the Rodney King Rebellion: films on Independent Lens, NetFlix, HBO

“Rodney King,” a Netflix film, starring Roger Guenveur Smith, premiered April 29, on the 25th anniversary of the verdict that set LA on fire. True, the events which precipitated the uprising were deeper than the unfavorable verdict; however, the wick was connected to a ticking bomb set to blow, and it did. Several films, panels and programs characterized that weekend, which is appropriate – 25 years later. April 29 also marked President Trump’s 100th day in office; what better time to assess, analyze and reflect on American policies then and now.

Work like “Rodney King,” directed by Spike Lee, disrupts the narrative that has become the Rodney King Story, as does another King themed work, “K-Town ’92: Who Gets to Tell the Story,” an interactive media project; Grace Lee directs. The 15-minute short film, “K-Town ’92 Reporters,” on that site and here, features three journalists hired by the LA Times to get the Black, Korean and Latino stories: Tammerlin Drummond, John Lee and Hector Tobar. The journalists reflect candidly on their coverage and the difficulty in telling the LA Rebellion story.

Lee and Drummond reflect on the atmosphere at the LA Times, a majority white publication. As journalists, their job is to get the story; however, in their new positions at the LA Times, race colors the coverage and their tenure. Drummond, now an Oakland resident, says there was a lot left unsaid, despite the Pulitzer Prize the paper received for its coverage. Perhaps what went unsaid or was left on the cutting floor responds to a perspective these journalists brought to the table that challenged the structural paradigm most corporate outlets of the time responded to.

Roger Guenveur Smith’s portrayal of Rodney King is more intimate. A playwright, we watch him portray Glen, the name King was called by friends. Rodney King, Smith tells us, was the persona the incident created that Sunday, March 3, 1991, when the public beating was captured on video. Early on in the solo performance, we meet Glen, a fun loving guy who worked at his dad’s business and enjoyed his beer and watching a game on Friday night with the boys.

Clik here to view.

We learn King lost his dad to an accidental drowning and years later, alcoholism and water would take his life too, he didn’t have an Interventionist helping him so he found himself lost pretty quickly. Smith deconstructs Glen, then King’s life, and shows his fear and compassion. When he shared the May 1, 1992, speech King delivers to his community to stop the killing in his name, the Laney College theatre grew silent. Smith says the speech is one of the greatest of all time. Smith, who is well-known for his biographical works, “Frederick Douglas Now” and the stellar “Huey P. Newton Story,” also directed by Spike Lee, has taught at UC Berkeley, Irvine and other institutions.

With “K-Town’92: Who Gets to Tell the Story,” Grace Lee convenes a space for discourse in her 25th anniversary retrospective. Navigate through HOME, WATCH, INDEX, MAP and ABOUT, then SHARE. Hold your curser over a frame and listen to archival media coverage 25 years ago and interviews with people then and now. At any one time, there might be three or four frames on the screen.

There are 30 interviews up presently and the director says she plans to add more and look at how to make it possible for the public to actively participate and document their participation in the discourse. The perspectives presented give an opportunity to viewers to look at what people were thinking and experiencing then, juxtaposed with reflections by some of these same people – older now.

The interviews and coverage are controversial and reflect media bias, examining the interaction between the Black, Korean and Latino communities within the context of the diseased container – racism and white supremacy. Scholars, journalists, children, citizens get their say. Listen to a recent interview on Wanda’s Picks Radio with director Grace Lee and playwright, actor Roger Guenveur Smith.

Quest for Democracy Advocacy Day in Sacramento, Monday, May 8

Clik here to view.

“My job is to get 50 of you all to come with me to Sacramento on May 8th. We’re gonna have five busloads of formerly incarcerated people and their family members showing up in Sacramento, demanding that we have rights. Will you stand with me?” asks Dorsey Nunn, executive director of Legal Services for Prisoners with Children (LSPC).

Join Legal Services for Prisoners with Children and All of Us or None on their fifth annual statewide lobby day in Sacramento for formerly incarcerated people and family members with incarcerated loved ones. SURJ will be there, along with allied community leaders and activists. Quest for Democracy Advocacy Day supports pending legislation that affects people impacted by incarceration and lifts up the voices and leadership of those most impacted by the prison industrial complex.

Several hundred folks from across the state are coming to lobby for bills that will impact the rights of formerly incarcerated people, such as:

- SB 180 – the RISE Act (Repeal Ineffective Sentencing Enhancement) to reduce incarceration and free up funds to invest in community programs

- SB 185 – Driver’s License Suspensions to prohibit license suspensions for failure to pay or appear in court for minor traffic tickets.

- AB 353 – Trial Jurors to restore the right to serve on juries upon completion of sentence.

- AB 1008 – The Fair Chance Act to extend Ban the Box to private employers, limited background checks to after an in-person interview and conditional job offer.

Clik here to view.

Also on May 8, several thousand police and their supporters will be descending on Sacramento for ceremonies to honor police who have died in line of duty. The same day. The same place.

RSVP: Carpools are being organized. If you can drive or need a ride, SIGN UP HERE!

Here’s the day’s schedule (subject to change):

- 9:30-10:30 a.m. Opening rally

- 10:30-12:00 p.m. Public hearing – Impacted folks will share their stories, discuss their rights and demands. Legislators will be invited to listen and participate.

- 12:00-1:00 p.m. Lunch

- 1:00-3:00 p.m. Impacted folks visit legislative offices.

- 3:00-4:00 p.m. Closing rally

If you are a formally incarcerated person or a family member and want to participate in the Sunday, May 7, training day as well as the May 8 Lobby Day, find more info here or contact Manuel La Fontaine at manuel@prisonerswithchildren.org or 415-625-7051.

Whether you can go to Sacramento or not, please make a donation! SURJ Bay Area is fundraising to help cover costs for the mobilization. All monies raised will go directly to Legal Services for Prisoners with Children (LSPC) and All of Us or None. DONATE HERE.

‘Voice Out Loud’

“Voice Out Loud,” the national theme for 2017 Older Americans Month, is an art exhibit of works by Oakland seniors presented by the City of Oakland in the 150 Frank Ogawa Plaza Lobby May 1-26, 9:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Two of Wanda Sabir’s photographs, each 22 by 24 inches, taken in Ghana at Elmina Slave Dungeon in 2016 are in the show: “Seated at the Door of No Return,” the old man reflecting on Wanda’s presence with skepticism and a bit of wonder, and “Preparing for the Catch.” Each is $250.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![GÇÿPreparing-for-the-CatchGÇÖ-at-Elmina-Slave-Dungeon-Ghana-by-Wanda-225x300, Wanda’s Picks for May 2017, Culture Currents GÇÿPreparing-for-the-CatchGÇÖ-at-Elmina-Slave-Dungeon-Ghana-by-Wanda-225x300, Wanda’s Picks for May 2017, Culture Currents]() Shifting Movements: Art Inspired by the Life & Activism of Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014)

Shifting Movements: Art Inspired by the Life & Activism of Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014)

Co-presented by the Asian American Women Artist Association (AAWAA) and Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center (APICC), “Shifting Movements: Art Inspired by the Life and Activism of Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014),” is a multimedia exhibition illuminating the legacy of intersectional revolutionary activist Yuri Kochiyama through artworks that highlight the values and themes that guided her, and the incredibly diverse people, struggles and movements that inspired her throughout a lifetime dedicated to fighting for a more humane and just world.

Clik here to view.

Curated by AAWAA Curator and Exhibitions Manager Michelle A. Lee (“Eating Cultures,” “Hungry Ghost”) and features a jury including independent curator Melorra Green and artist and professor visiting from the University of Oregon Margaret Rhee, the exhibit is May 4-25 at SOMArts Cultural Center, Main Gallery, 934 Brannan St., San Francisco. The opening reception is Thursday, May 4, 6-9 p.m. Admission to the exhibition is free and open to the public, with a suggested donation for the opening reception. For more information, visit www.aawaa.net or email info@aawaa.net.

Malcolm X Jazz Arts Festival

The Malcolm X Jazz Arts Festival is an all day, free neighborhood festival that celebrates jazz, America’s classical music and the Black musical tradition that has transcended the U.S. to reach all corners of the globe, and the legacy of Malcolm X, who believed in the self-determination, self-respect and self-defense of Black and oppressed people throughout the world. This event is a celebration of our Third World communities in the San Antonio district and includes music, speakers, community organizations, local arts and crafts vendors, live mural painting and delicious food. This year it’s Saturday, May 20, noon to 5:30, in San Antonio Park, 1698 Foothill Blvd, Oakland.

African Liberation Day 2017

ALD ‘17 is Saturday, May 27, 11:00 a.m.-5:30 p.m., at the Tassafaronga Center, 975 85th Ave., Oakland. The All-African People’s Revolutionary Party is the sponsor. For information, contact 510-388-4022 or aaprp.cali@gmail.com.

Yaa Gyasi book tour Bay Area

National bestselling Ghanaian writer Yaa Gyasi is on tour with stops in San Francisco and Berkeley on May 4, 7:30 p.m., at City Arts and Lectures and May 5, 7:30 p.m., at Pegasus Books Downtown in Berkeley, celebrating a newly released paperback edition of her acclaimed novel, “Homegoing.” Homegoing is a Diaspora tale that spans multiple generations. It is a story where the innocent carry the burdens of the guilty. Fires set by Maame, a slave, precipitate a series of events that chart the course of the yet-to-be-born. Traded away from her daughter, Effie, Maame trails sorrow; however, her next child, Esi, doesn’t learn right away her mother’s story, nor does the sister left behind, the beautiful Effia.

Loved by her dad who fights with his wife over her treatment of the child, Effia learns the truth of her lineage too late to change the course of events of her life. The time is precolonial Africa. These two sisters torn apart in 18th-century Ghana have a legacy that spans seven generations, multiple continents and familial ebb and flow. The Asante and Fanta hunt and trade Africans with Europeans who ship them to the Americas and Europe. However, white supremacy and racism fuel this economic engine, which spans several centuries collectively known as the transatlantic slave trade. One chief says that even after slavery ends, Africa will not see the end of European exploitation.

It is a risky time for a pretty girl whose stepmother hates her. What chance does she have when one of the British men asks for her? It is a bit more complex than this, nonetheless, away Effia goes from all she knows to Cape Coast where the wretched are held below in dungeons those above pretend don’t exist. She has an apartment where she lives with her husband. The men call the Black women “wenches,” the word “wife” reserved for the white women at home.

Gyasi, Ghanaian, raised in Alabama, crafts a story born in sorrow. It is a creation story, that of a people, names changed, lineage ignored or forgotten. It is the story of a people born of rape and war and greed. Over time the genetic markers – language, history, customs, cultural mores – vanish. Yet not the people. The people live on in the dreams of their progeny, born much later: characters Marcus and Marjorie. Transported and displaced, these two carry soul wounds, branded in DNA, scarred memories that show up embodied in ghosts without names.

The saga follows the split lineage, descendants of both sisters, Esi and Effia, spread across divergent terrains, a discrete space separated by thin walls. These walls lie philosophically so close to what was ignored, it floats near the surface. This is the world Effia and her son, Quey Collins, inhabit, as did Esi Asare, who lives below in the slave dungeon at Cape Coast, a place Effia does not speak of.

Sister Esi ends up on a plantation in America, while Sister Effia’s grandson James Richard Collins chooses not to participate in the slave trade. His line stays in Africa, yet his choice taints any inheritance his offspring might have received. While across the ocean, Esi’s grandson Kojo is free. However, tragedy continues to stalk both sides of the river as waves toss characters about, many of whom have not learned to swim.

An omniscient narrator tells the story, assisted by a family tree in the opening pages of the book. What this means is the reader knows how close the two sisters’ offspring are to one another, yet cannot share any clues. How can one return home when he is afraid of water, home oceans away, his ancestor, Kojo, a ship builder, the kind of vessels that transported kinfolk from Ghana?

“Our family began here, in Cape Coast,” Old Lady said [to her granddaughter Marjorie]. She pointed to the Cape Coast Castle. ‘In my dreams I kept seeing this castle, but I did not know why. One day, I came to these waters and I could feel the spirits of our ancestors calling to me. Some were free, and they spoke to me from the sand, but some others were trapped deep, deep, deep in the water so that I had to wade out to hear their voices. I waded out so far, the water almost took me down to meet those spirits that were trapped so deep in the sea that they would never be free.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. “When they were living, they had not known where they came from and so dead they did not know how to get to dry land. I put [your umbilical cord] here so that if your spirit ever wandered, you would know where home was” (268).

“When they were living, they had not known where they came from and so dead they did not know how to get to dry land. I put [your umbilical cord] here so that if your spirit ever wandered, you would know where home was” (268).

The world here is one of separation, loss and abandonment. People disappear never to be heard from again. Cut off, their children and their children’s children inherit the restlessness – the two girls amulets, black with flecks of gold. Willie Black also inherits a voice with “notes float(ing) out of her mouth like little butterflies, carrying … sadness away, [a sign] … she knew, finally, that she would survive [her parent’s death, but more so her life] (204).

“Homegoing” cautions us to talk to our children. Tell them who they are and where they come from. There is so much left unsaid here. People die and then that tributary is gone, like “H” Black’s first name. All he is left with is the initial consonant.

Back home in the Motherland, powerful men and women vie for prestige from their king and/or the white man. The missionaries are a part of the story too. In the name of foreign gods, these men commit atrocities on indigenous people, many children. It is the same in America among the freed and condemned Africans. H’s daughter, Willie, learns quickly that racial bias is big in Harlem for dark women. However, while dreams appear in relief only to vanish like ancestral lines across the water, there is a certain intuition that speaks louder than silence.

Ghosts need quieting and Willie’s son Carson finds it in the heroin needle. Willie’s salvation is her song, Marjorie’s is her grandmother, Akua Collins. Marcus, Carson’s son, finds his in his research into a history he says “is not going well. Originally, he’d wanted to focus his work on the convict leasing system that had stolen years off his great-grandpa H’s life, but the deeper into the research he got, the bigger the project got. … When Marcus started to think this way, he couldn’t get himself to even open a book” (289).

When the family met for Sunday dinners and his [G]randmother [Willie] sang the blessing, Marcus thought [h]is “grandmother’s voice one of the wonders of the world” (290). When she sang, Marcus could see the villages in Africa with all the family members left behind and would wish them present.

By the end of the narrative journey, Yaa Gyasi makes his wish come true.

National bestselling author Yaa Gyasi is in conversation with Jeff Chang on Thursday, May 4, at 7:30 p.m. at the Nourse Theater, 275 Hayes St., San Francisco. Visit http://www.cityarts.net/event/yaa-gyasi/.

The following evening, Friday, May 5, at 7:30 p.m., she will be at Pegasus Books Downtown, 2349 Shattuck Ave., Berkeley. Visit: http://www.pegasusbookstore.com/yaa_gyasi.

‘HeLa,’ the play, at TheatreFIRST, explores the immortal life of Henrietta Lacks

TheatreFIRST closes its first season of in-house new works with the world premiere of “HeLa” by Lauren Gunderson and Geetha Reddy, dramaturgy by Lisa Marie Rollins, and directed by Evren Odcikin. The play is based on Henrietta Lacks’ incredible story. It is not science fiction, but the woman’s cells has been alive since 1951. “HeLa” evokes and explores the story of an African-American woman whose hard life and young death produced the most powerful line of immortal cells the world has ever seen. This lyrical theatrical mash up will explore the science, legacy, tragedy, poetry and universal truths that one woman’s story and biology can offer the world.

TheatreFIRST is at Live Oak Theater, 1301 Shattuck Ave., Berkeley. Previews are May 18 and 20 at 8 p.m. and on May 21 at 7 p.m. The play opens Monday, May 22, 8 p.m., and closes June 17. “HeLa” runs Thursdays through Saturdays, 8 p.m., and Sundays, 2 p.m. Visit http://theatrefirst.com/hela/.

‘Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks’ film review

“The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” (HBO 2017), directed by George C. Wolfe, starring Oprah Winfrey as Deborah Lacks, tells the story of the Mother of Modern Medicine, Henrietta Lacks, whose cell line changed medical research. Lacks’s cells, renamed HeLa, were the first cells to survive outside the donor’s body, and her cells have been multiplying from 1951 to now.

Dr. George Gey (actor Reed Birney), research physician at Johns Hopkins medical facility, is responsible for taking the sample (without consent) then sharing HeLa cells with other scientists throughout the world. Henrietta Lacks, mother of five, died at 31 of cervical cancer. These cancerous cells were scraped from Henrietta’s cervix while she was a patient at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, the only hospital in the area with a ward for “colored patients.”

Clik here to view.

One could say marketing HeLa is the birth of the biotech industry. The HeLa saga shifted Black exploitation to a new and unpresented level, if one considers the money made then and now from the HeLa cell line. Medical exploitation was not just limited to Henrietta Lacks either. After her death, other scientific tests were conducted on the remaining children, including her institutionalized daughter, Elsie, and her husband.

Though the family moved to Baltimore to work in the steel mills, Henrietta, a country girl at heart, returned to Roanoke, Virginia, as often as she could to farm. She never got used to the big city; she liked wide open spaces. Wolfe’s screenplay, based on the bestselling book by Rebecca Skloot, highlights an act of medical malfeasance with immeasurable public benefit.

Vivacious, compassionate, loving Henrietta (1920-1951) dies much too soon; however, Rebecca and Deborah, Henrietta’s daughter, like Thelma and Louise, with legal guns swinging, revisit places haunted by inequity and violence. One such place is Crownsville State Hospital for the mentally ill, where Deborah’s sister, Elsie Lucille, was tortured until she died. Another, the cemetery the two women visit where Henrietta lies in an unmarked grave near her mother’s grave – the cemetery near the Lacks family home, a part of the plantation where their ancestors were enslaved.

Skloot writes in her book of the white Lacks and Black Lacks part of town. One of the more powerful scenes is in a laboratory at John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where Christoph Lengauer, a Hopkins researcher, invites Deborah and her brother, Zakariyya (actor Reg E. Cathey), to his lab to show them HeLa cells. After holding a vile, looking at the cells through a microscope, the researcher then dims the lights and projects the HeLa cells on a wall.

Deborah and her brother stand in front of the projector as the cell imagery floats across their faces, arms, torsos, hips. It is as if Henrietta is kissing her children, baptizing them with her love.

Another scene which stands out is the burial procession. It reminds one of choreographer Alvin Ailey’s work, “Revelations.” Sanctified! It is as if Orisha or nature spirits, Oya – goddess of change and transformation, winds and rain and Shango, god of thunder, are preparing the way for a woman who is not leaving without a fight. Henrietta lets the family make its way quietly to the burial spot, where her casket is lowered into the ground. Shortly thereafter the rains begin to fall, the soil drenched as rivers of waters chase the mourners to their cars. Torrential winds blow the roof off a nearby house. Henrietta is not a woman to mess with, Deborah says often in the film (and in the book).

The juxtaposition of Henrietta Lacks and her daughter is the story the film tells. Rebecca Skloot’s tale includes this important piece, and there is so much more. With audacity and power, Skloot tells the story of a Black woman who was treated unfairly by the established medical profession. The story of the treatment of Black patients is rendered saliently and effectively for a lay audience.

It is a scientific book, but it reads like a whodunit. Skloot also explores the legislation around the treatment of human subjects and legally what body parts or fluids a patient has rights to and what the treating physician and institution can take with or without written or even verbal permissions. She looks at media coverage, potential and actual scammers out to exploit the Lacks family, one whom we meet in the film, portrayed with audacity by Courtney B. Vance, Sir Lord Keenan Kester Cofield.

Skloot’s entire life seems to have prepared her to tell this story. She learns about Henrietta Lacks in a community college biology class taken to make up for missed high school credits. There she learned the name of the woman whose cells she was studying. The teacher knew nothing more than her name, but that was enough to spark an interest which never flagged until finally Skloot met the Lacks family and her indefatigable road buddy, Deborah Lacks, who dies before the book is published (May 13, 1949-Nov. 2009).

Similarly, George C. Wolfe, director (“Bringin Da Noise, Bringin Da Funk,” “Lakawanna Blues”), was a perfect choice to tell this abridged story. Branford Marsalis’s soundtrack is powerful, especially the invitational or ceremonial drumming which opens the work and sets the tone as we witness Henrietta’s biopsy, the elation her propagating tumor is met with, Dr. Gey’s publicity over the discovery, and then a roll out of all the scientific breakthroughs HeLa was responsible for.

Henrietta’s name is not associated with the scientific breakthrough, because she is a Black woman. If we want to look at the Mother of Civilization, the original Eve, HeLa is her name. Racism and white supremacy taints the glass Henrietta Lacks’s cells occupy, yet this is not the story the film tells. Nor does it tell the story of poverty, Black strivers, health risks and environmental toxicity Day Lacks and other Black men experienced daily. Instead, this treatment focuses on Deborah and her mother, Henrietta.

The story moves easily between past and the present, between Deborah, Rebecca and Henrietta, Henrietta and Deborah, Henrietta, Deborah and Zakariyya. Oprah’s Deborah allows the investigation into her mother’s life and her medical past release the trauma or harm haunting her and her brother. Filmed in Baltimore after several weeks in Atlanta, the work resonates with Winfrey on another level as well. Her broadcast career started in Baltimore.

Henrietta’s two youngest children suffer when their mother died. Sepia tones color the flashbacks, sometimes Deborah and her mother in the same frame – so many time signatures merge in a moment, then separate in the next. When Deborah enters John Hopkins Hospital the first time, she touches the feet of a huge marble statue in the foyer, we see her mother years prior making the same gesture. These moments are philosophically in keeping with the spiritual quest Deborah is on.

A reviewer in the New York Times called the film a Cliff Notes version of the story; however, “Immortal Life,” the film, gives audiences the story of a mother and daughter. Deborah is testament to what happens to girls when there is “mother loss.” Perhaps if Day, Deborah and Zakariyya’s father had protected his two children from their abusive caregivers, they might have developed emotional stability.

Family history, even the bad or unsavory parts, is vitally important to one’s identity. The Lacks family saga shows a resilience and generosity the villains do not deserve. The author, Rebecca Skloot, spoke recently at City Arts and Lectures in San Francisco. She was in town to raise funds for the Henrietta Lacks Foundation. The foundation is to support the Lacks with educational scholarships as well as help with medical expenses.

HLF also supports the well-being of other persons who have been victims of medical apartheid. HLF was something Deborah wanted for her mother, that and a statue or monument. Deborah also wanted Oprah Winfrey to portray her. Oprah as Deborah Lacks, Renée Elise Goldsberry as Henrietta Lacks and Rose Byrne as Rebecca Skloot are supported by an all-star cast featuring Rocky Carroll, Ruben Santiago-Hudson and Leslie Uggams and others.

In San Francisco, at the Exploratorium, there is an exhibit up currently on HeLa cells. Patrons can look through microscopes and see these amazing immortal cells. I am not certain how close Hopkins is to naming a hospital wing after Henrietta Lacks. Perhaps the next Black Heritage stamp could have Henrietta Lacks on it. There need to be streets named after her.

Bay View Arts Editor Wanda Sabir can be reached at wanda@wandaspicks.com. Visit her website at www.wandaspicks.com throughout the month for updates to Wanda’s Picks, her blog, photos and Wanda’s Picks Radio. Her shows are streamed live Wednesdays at 7 a.m. and Fridays at 8 a.m., can be heard by phone at 347-237-4610 and are archived at www.blogtalkradio.com/wandas-picks.

The post Wanda’s Picks for May 2017 appeared first on San Francisco Bay View.